Introduction

This is a text on the internet. There are many like it but this one is mine;

and yours;

and everyones;

ever changing;

never finished.

I'm going on an adventure, to think and write about the landscape we're currently1 in and the changes to our collective way of thinking about ourselves and the society2 we're part of. Thinking back, the last two decades marked a drastic shift in the ways individuals and groups communicate with each other in a modern world. The expectation that everyone around us knows how to use (and misuse) the new tools of communication and information reveals the ambiguity of the underlying concepts. With the implementation of this ambiguity into fixed systems – built mostly by private companies – our society also seem to lose the agency to advance themselves in the future. This is a pessimistic view of digitization and falls in line with the way of thinking of the Swing Riots in the 1830s. One could think with the rhetoric used in news articles3 discussing pitfalls and setbacks – from the point of view of companies working in these fields – that an "Orwellian Dystopia" is the only logical outcome. A worrying outlook, but this not the whole story and much of it is still in our – individual and collective – hands.

Maybe these changes we're all currently experiencing give us an opportunity not just to reflect on the new implementations of everyday interactions, but also on the interactions and concepts they're based on. Grand shifts in society tend to trigger discussions around specific variables and rarely society in its entirety, but that is exactly what we are currently undergoing as we try to translate more and more aspects and interactions of our everyday life into the digital realm under the flag of efficiency. The result is a deadening confusion amongst our peers and ourselves.

This essay doesn't only give a highly subjective and opinionated view of the matters at hand, but also challenge the reader with a few obstacles along the way. The structure isn't fixed, the conclusions and views are ever shifting – even while you're currently reading this –, and over time, there will be additional changes I and hopefully others will supply to this essay. You can follow and judge the progression of this construct on the Git-Repository4 or more specifically in the commit history.

Because of the previously described nature of this essay, I am already providing my conclusion of the following paragraphs: Dividing opinions regarding the internet into dystopian or utopian camps misses the opportunity to think of something in between: The act of translation into the digital realm itself. This act – combined with the fact that any practice of abstraction and/or translation has to deal with a certain amount of loss of information – offers a working surface on which to place critique that can lead to reflection on the concept being translated regardless if it is revering to the "original" concept or the newly installed digital one. And right now, while we talk about "digitization", is the moment to work on this theory before we are unable to distinguish between the implementation and the practice itself, and the translation becomes the replacing instance. - When we criticise Facebook, we can think about friendship and social interactions. - When we criticise Twitter, we can think about how we get our news. - When we criticise Google, we can think about knowledge.

About

In the beginning, this essay was written by Fernando Obieta in his second Semester at the Zurich University of the Arts enrolled in the masters program "Transdisciplinary Studies in the Arts". Special Thanks to: Prof. Irene Vögeli, Basil Rogger, Jil Sanchez, Nina Calderone, Silvan Jeger and Marco Wettach.

The digital space

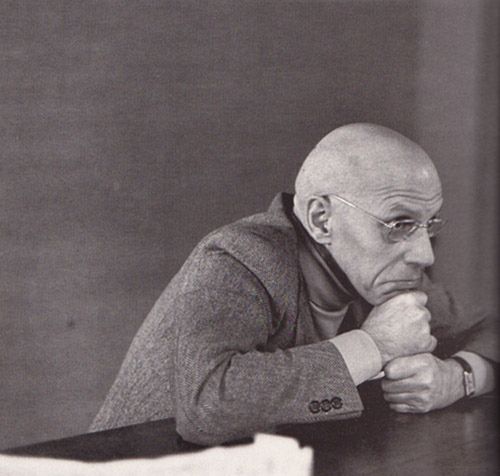

When we think about "space" we most commonly use it in two contexts: a physically existing space located in the world or a metaphorical one which often refers to time. The digital space is like no other we have encountered before because it doesn't behave like the spaces it is compared to, which are encapsulated within themselves, but penetrates nearly all of them in our physical world. It acts as an additional layer within and spanning across, which can also be understood as an additional layer of society. In 1967, Michel Foucault described his concept of the Heterotopia :

"There are also, probably in every culture, in every civilization, real places—places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society—which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality. Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, I shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias."

Michel Foucault 19675

The description Foucault provides fits a romantic description of the internet for the forty years before it became part of our everyday life. One could argue that the internet isn't "real" and only exists as a form of interpretation and translation and isn't bound to a physical space6 like Foucault's ships or brothels. The way that people and the media refer to the "digital space" reveals an underlying misapprehension that we could escape from or ignore this space.

"Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable. In general, the heterotopic site is not freely accessible like a public place. Either the entry is compulsory, as in the case of entering a barracks or a prison, or else the individual has to submit to rites and purifications. To get in one must have a certain permission and make certain gestures. [...]"

Michel Foucault 19677

The submission to these new forms of communication is becoming a requirement to stay relevant within society, with jobs requiring digital application in fields which do not require this specific skillset in their practice. To a certain extent, the ability to navigate through the digital forms of communication and interaction became the new centerpiece our education, which is concerned with and struggling to give people the means to comprehend our world. But education favors the usage and not understanding of or reflection on these "tools". If we submit to these new forms of communication, we are actively dividing our society into "users of technology" and "absentees". The threshold one has to overcome to communicate with someone for longer than just a few interactions in person without – for example – a smartphone8 or availability through instant messaging or e-mail, is higher with someone who's using these tools like you right now. Maybe we are constantly peer-pressuring other people – without specifically intending to do so – to join our digital heterotopia of efficiency9.

So maybe the compulsory "feeling" that arises, that you're "missing out" when you're not part of this digital "revolution", forces us to define a position towards this digital space. I argue that the individual choice one makes isn't the interesting thing, but the nature of our time that becomes part of our everyday discourse of having to make a choice how one stands in the digital space.

Do you have Facebook, Instagram, GMail, Skype, WhatsApp, Twitter, Telegram, Signal, Threema, YouTube, Netflix, HBO, Spotify, Apple Music, Dropbox, Reddit... why not? It's so useful!

- Have you seen my Instagram Story?

- Have you seen what Elon Musk posted on Twitter this morning?

- Are you coming to the party I've invited you to on Facebook?

- Did you watch the newest episode of "Game of Thrones" on HBO?

- Did you read my text about your assignment next week on WhatsApp?

Our private and social lives are more intertwined than ever before with these tools. They're telling us that we're relevant and part of society if we're using them; if we're following the people we admire and know; if we're showing the world who we actually are; if we're telling our story; and all of this not just inside an external isolated space with its own rules, but within a layer entangled with society and our everyday lives, abstracted from our past, present and – through absorption – also future concepts of interactions with each other.

From a system to a system

The translation of man-made concepts and systems into a computer system requires the hard choice of determining what an analogue value is as a digital one. 1s and 0s. Not every system we have in place can to be abstracted in such a form, and even though a few of them can be, there are the problems of man-made systems of responsibility and agency even in seemingly easy examples hard to pin down:

Tom Scott, 201410

If we can bring an interaction like in this example voiting into a digital form, with the promise of "better" integration for the people using it, why shouldn't we? The pretense might even be a noble one, but the impact and consequences might be unforeseeable, especially with something as delicate as human interaction. The example above about voting mechanisms illustrates that even man-made systems of representation and responsibility like the simple "yes" or "no" to a question posed by a government to its citizens is practically impossible without creating new forms of exploitation. I argue that it isn not solely about the shift in agency but also about the shift of responsibility from people with the knowledge of the context to programmers.

"I will say something about why to invent as well. Because you could see our work as experimental, or science fiction, or futuristic; but I would say - and others in the studio may not agree with me - that our design is essentially a political act. We design 'normative' products, normative being that you design for the world as it should be. Invention is always for the world as it should be, and not for the world you are in.

By designing it, it's a bit like the way the earth attracts the moon, and the moon attracts the earth just a tiny bit. Design these products and you'll move the world just slightly in that direction."

Matt Webb, 201211

Webb talks about designers here but the comparison to programmers is not far fetched, as the two professions deal with the same problems at hand, abstraction and translation into something people without the required knowledge could understand and use. So the question becomes rather than just a practical one of how one can convey the necessary information also one of ethics and of how one should convey the information. Each and every designed artefact isn't an "objective" representation of what is needed but the subjective understanding of its creators.

"We are quite willing to admit that technology is the extension of our organs. We knew it was the reduction of force. We had simply forgotten that it was also the delegation of our morality. The missing mass is before our eyes, everywhere present, in what we admiringly or scornfully call the world of efficiency and function. Do we lack morality in our technological societies? Not at all. Not only have we recuperated the mass that we lacked to complete our sum, but we can see that we are infinitely more moral than our predecessors."

Bruno Latour, 198912

Relocating the morality out of the individual into an artefact pushes the user of the artefact to follow the morality. The specific morality and its orientation isn't chosen by the user anymore but by the creators of the artefact. This way of thinking – organising morality, efficiency and risk – was the dream of cybernetics and systems theorists. An overspanning all-inclusive system which regulates all of its components with feedback-loops:

Adam Curtis, 2011, 28:00 – 36:0513

The level of complexity far overreaches the capacity of our understanding of how society and nature operate. But the belief in this vision, of a model to regulate and comprehend the world weare in lead to a "trust" in machines, which they will never be able to fulfill. A machine or system can never exceed its creators in their vision, only in efficiency, and this efficiency only scales the subjective understanding its creators have put into it and can't eradicate it14. But this misled trust in these "neutral" and "objective" machines averts the fact that they will never be able to "solve" our social challenges, which we will have to carry out ourselves now and in the future while these biased machines can only be what they were before: tools or an enhancement:

"Now, it might be that in any technological utopia which we have any real chance of creating, all individuals will remain constrained in important ways. In addition to the challenges of the physical frontiers, which might at this stage be receding into deep space as the posthuman civilization expands beyond its native planet, there are the challenges created by the existence of other posthumans, that is, the challenges of the social realm. Resources even in Plastic World would soon become scarce if population growth is exponential, but aside from material constraints, individual agents would face the constraints imposed on them by the choices and actions of other agents. Insofar as our goals are irreducibly social – for example to be loved, respected, given special attention or admiration, or to be allowed to spend time or to form exclusive bonds with the people we choose, or to have a say in what other people do – we would still be limited in our ability to achieve our goals. Thus, a being in Plastic World may be very far from omnipotent. Nevertheless, we may suppose that a large portion of the constraints we currently face have been lifted and that both our internal states and the world around us have become much more malleable to our wishes and desires."

Nick Bostrom, 200715

Maybe we're just following our system of hearing what we want to hear and only created a new terminology with the "filter-bubble" to escape responsibility.

Progress

It can be argued that the human "need" to receive, transfer, and share information as a survival mechanism finds its logical continuation in the internet. The efficient transfer from speech, to text in its physical form to a fluid accessible digital form divided into bits and bytes delivered to our screens is a causality followed by an ideology of constant progress as a society and species. But now the question arises what "progress" actually is:

Adam Curtis, 2016, 23:26 – 26:5516

When we apply the same logic Arkady and Boris Strugatsky coined with "HyperNormalisation" in Roadside Picnic, as depicted in Adam Curtis' documentary of the same name to our digital age, we can start to ask the question of how much of this is "progress" and what is just a more efficient way of implementing our pre-existing concepts. A lot of our interpersonal problems that arose the last decade are rooted in a lack of progress in our sociological concepts of communication. Of course we have Emojis now to better convey what we really mean, but the basis stayed the same. Our ways of communication were never meant to have an efficiency of this magnitude. - I wrote you a text on WhatsApp 15' ago. I saw that you've read it but you didn't reply! - 23:20 on a Sunday: Here's the assignment. Due by tomorrow at noon. - I saw that you're friends now with Laura on Facebook. You know I hate her!

Maybe we're just pretending that these forms of communication are "better" or "progress". They seem to make us more efficient but everything is also trying to get our attention and must be dealt with immediately. But if this thesis is true, why are we pretending? The only explanation I can think of is an empowered drive for validation and looking for the "best possible solution" for ourselves as an evolutionary drive.

In his book "The Insanity of Normality" the psychologist and psychoanalyst Arno Gruen is looking for a reasoning for this mode of behaviour and describes the empathetic nature of "wanting to be loved" and "wants to love others" in exchange for autonomy. We like to be guided towards these feelings and don't tend to reflect on how we achieve them in the process as long as they fulfill our desires. In this regard the shift towards the new forms of communication with their quick fixes of affirmation is almost logical.

Who is my avatar

Various science fiction writers described utopian or dystopian worlds in which society is deprived of reflection on their guiding systems. In Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World"17 the members of society pressure each other to take the happiness-inducing drug "soma". When one compares this drug to the pressure of availability and representation on social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram on which everyone is happy, everyone is successful and everyone is doing great things in their individual lives, it becomes clear that we are already doing the same thing. We force upon our individual selves the pressure of capitalization and quantification of each and every aspect of our lives, to show our peers that we're worth the "social capital" that we represent. But the dissonance between our presented selves and how – we think – we are is an age-old discussion in sociology and psychology of how we perceive ourselves. Social media gives us the means to do this in an orderly and structured fashion. You have the same amount of space as everyone else to fill up with as many things as you see fit to "correctly" show us who you actually are – or would like us to believe you are.

In his book "Alienation and Acceleration"18, Hartmut Rosa argues that the promise of the moderne era is the autonomy to decide – individually and collectively – what self-determination is. Who we are and how we want to live. But this aim toward autonomy is clouded by the rising alienation and acceleration (the title of his book) we developed alongside. He further describes this situation as a "competitive-society", in which the highest aim is to be happier than your peers, in which the sole goal is to like and not to reflect, where the end justifies the means and one superlative overthrows the next. In this situation, who you are cannott always be represented in a system in which the only reaction is a "like" and the separation between who you are online and in the physical world becomes inevitable.

We've created a perfect new world of discipline through each other and these tools. Everyone stays in their lane and those who don't are not part of our modern world. So your only option is self-control, as Gilles Deleuze describes in a further development of Michel Foucault's thoughts on power and control:

"The socio-technological study of the mechanisms of control, grasped at their inception, would have to be categorical and to describe what is already in the process of substitution for the disciplinary sites of enclosure, whose crisis is everywhere proclaimed. lt may be that older methods, borrowed from the former societies of sovereignty, will return to the fore, but with the necessary modifications. What counts is that we are at the beginning of something."

[...]

"Can we already grasp the rough outlines of these coming forms, capable of threatening the joys of marketing? Many young people strangely boast of being "motivated"; they re-request apprenticeships and permanent training. It's up to them to discover what they're being made to serve, just as their elders discovered, not without difficulty, the telos of the disciplines. The coils of a serpent are even more complex than the burrows of a molehill."

Gilles Deleuze, 199219

And we're discovering first hand what our "marketing of the self" is creating. A society in permanent dependency to reactions through arbitrary feedback which isn't able to replace inter-human-interaction.

Any gesture of refusal short of going off the grid entirely will be still less likely to result in the desired independence from the process of intimate, persistent oversight and management now loose in the world. Just as whatever degree of freedom to act we enjoy is already sharply undercut by commercial pressures, and the choices made in aggregate by others, so too will our scope of action be constrained by the shape of the place that is left for us by the functioning of automated and algorithmic systems, the new shape of the natural, the ordinary and the obvious – for that is how hegemony works. If neoliberalism, like any hegemonic system, produced subjects with characteristic affects, desires, values, instincts and modes of expression, and those subjects came in time to constitute virtually the entirety of the social environment any of us experience, it's hard to see how matters could be any different in the wake of the posthuman turn. It is exceedingly hard to outright refuse something which has become part of you – and made you part of it – in the most literal way, right down to the molecular composition of your body and the content of your dreams.

Adam Greenfield, 201720

But don't be afraid. If you come back, your avatar will still be here.

which is – when this project works in the intended way – now and in the future ↩︎

In my case right now: the German speaking part of Switzerland in April 2019 ↩︎

like the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal 2018, the leaks surrounding surveilance which are on an all time high since the Snowden leaks in 2013, the list is long... ↩︎

a version control system used and misused by programmers all over the world for sharing and collaborating on a variety of code based projects ↩︎

Michel Foucault, 1967. Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, from Architecture / Mouvement / Continuité, October, 1984;(“Des Espace Autres,” March 1967 Translated from the French by Jay Miskowiec), p. 3-4 ↩︎

at least, not since the era of the "internet cafes" died in the early 2000s ↩︎

Michel Foucault, 1967. Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, from Architecture / Mouvement / Continuité, 1984; (“Des Espace Autres,” March 1967 Translated from the French by Jay Miskowiec), p. 7 ↩︎

this is going to be crucial to update in the future! Who knows when the next thing will take over... ↩︎

The fact that you're reading this right now on a website, in a browser, on a device (like a computer or a smartphone) implies that you're at least to a certain extent part of this ↩︎

Computerphile, Tom Scott, 2014. Why Electronic Voting is a BAD Idea, YouTube ↩︎

Matt Webb, 2012. The near future inventor in: Rory Hyde, Future Practice: Conversations from the Edge of Architecture, New York: Routledge, 2012 ↩︎

Bruno Latour, 1989. The Moral Dilemmas of a Safety-belt from: La Ceinture de sécurité”, in Alliage N°1 p.21-27. Traduction inédite en anglais, unpublished English translation by Lydia Davis, p. 6 ↩︎

Adam Curtis, 2016. All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace - Episode 2 - The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts, BBC, 28:00 – 36:05 ↩︎

Like the many times programs operated by "machine learning" – to which people often falsely refer to as "A.I." – created racist or biased outcomes ↩︎

Adam Curtis, 2016. HyperNormalisation, BBC, 23:26 – 26:55 ↩︎

Huxley, Aldous, 1931. Brave new world, New York: Everyman's Library. ↩︎

Hartmut Rosa, 2010. Alienation and Acceleration: Towards a Critical Theory of Late-Modern Temporality, Aarhus University Press ↩︎

Gilles Deleuze, 1992. Postscript on the Societies of Control, MIT-Press, p. 7 ↩︎

Adam Greenfield, 2018. Radical technologies : the design of everyday life London: Verso., p. 310-311 ↩︎